- Home

- Wyclef Jean

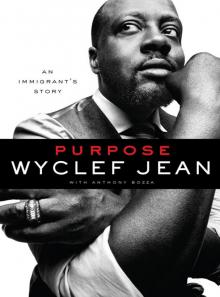

Purpose Page 3

Purpose Read online

Page 3

At that moment, I lost it. I grabbed him by the collar. “One of your own men said you’re not burying the people in their own holes. Don’t you lie to me! One hole for each body that I gave you, do you understand?”

“I understand!”

I turned to FaFa. “Stay here and make sure each one of them gets their own grave.”

“I’ll dig them myself if I have to,” FaFa said. That is the kind of man he was.

After we returned, FaFa left in his pickup truck to begin taking bodies from the rubble to the graveyard; it was a four-wheeled ferry for the dead. During one of these trips, he was carjacked by some gangbangers. He refused to get out of the truck, so they shot him in the chest twice and drove off. We know this because the guy riding with FaFa slipped out the other door and got away.

When the guy who survived came to us and told us what had happened I went completely insane. I forgot who I was, all that I had done, everything. I didn’t care about any of it; I only cared about killing FaFa’s killers. I can’t lie. I decided that I probably wouldn’t make it back to America and in that moment I was okay with that. Nothing else mattered. I was going to kill them or die trying because the injustice of his death was too much for me to bear.

It wasn’t a fantasy; I was ready and able to do this. I had all kind of guns and weapons at my disposal and my only mission became putting FaFa’s killers underground. As I got ready to leave with my team, my wife started screaming at me.

“You can’t do this! You can’t do this!”

“Yes I can!”

“Keep in mind why you’re here! Keep in mind what you came here for. There is a lot of tension but you have to stay above it! You are going to ruin everything you’ve done here over this! Stop it right now. You will destroy your life in one second. These people need you. Think of them—not of yourself!”

“Get off of me! I’m going to handle this.”

She was right of course. And I heard her, but I wasn’t going to stop what I was doing. My wife is such a good woman that in the end she came along with us rather than see me go out there alone. She’s my ride or die. She and her friend Cynthia Debeaux came along. And with those two on your side, you don’t need anyone else.

We loaded up the car with arms and went out to find the killer. We drove around for hours but we never found a trace. We couldn’t find the truck; we didn’t find his body. We didn’t find anything. The killers were so scared of retribution that they made FaFa just disappear. To this day his body has never been recovered and nothing else has been learned about who did it. They must have known from the start that if we tracked down FaFa’s body, we would figure out who killed him and come for them.

Over the next three days my wife and I spent our waking hours loading bodies onto trucks until our hands burned. When someone dies, the body releases all of its toxins. When you pile bodies on top of each other under the blazing sun, those toxins become a corrosive acid, as the chemical reaction that comes with rot sets in. We worked through it, washing our hands as often as we could, because we had no gloves.

We spent our nights strategizing on a large scale, plotting how we could bring international aid into the country as quickly as possible. After a few days on the ground, Yéle was up again and running, providing safe drinking water and food, and clearing the streets of the dead before disease took hold. There would be no end to the work, but I realized that I could do greater good back in America, promoting the relief effort.

I did not know how long I had been gone as I set out for the airport, because it was all still a blur. In front of La Villa Créole, I saw a member of my Yéle family that I’d not seen since my first day on the ground.

“How are you, brother?” I asked him.

“She lived, Clef,” he said, smiling at me. I didn’t know whom he was talking about at first.

“The girl, in the clinic, she lived.”

Her face came to me, and that intense moment which was so intense returned. It had happened just a few days ago, but I felt like I was recalling something from long ago. “I’m so glad to hear that, brother. I’m glad she’s alright.”

“It’s better than that, Clef. She can walk, too.”

The girl we had pulled from the rubble—she had survived. Her legs were not paralyzed; they were only traumatized, the nerves damaged by the impact of the debris. The numbness was so severe that her legs were temporarily useless, but after a few days the feeling came back, and after that her motor skills. She had grown strong and left her hospital bed.

She didn’t go far though, because she had nowhere to go. She had been saved and she was grateful, so she did the only thing that made sense to her: she helped the doctors to repay her debt to them. She worked to rebuild, in whatever small way she could, the spirit of Haiti. In the days and months that followed, I kept her memory in my heart. Like an eternal flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, it gave me the strength to go on and to never forget that there was always more work to do. No one could do it alone; we would all need to lean on each other.

1

THE VILLAGE

I was born in Croix-des-Bouquets, a village that lies in the Ouest Department of Haiti, about ten miles from the nation’s capital, Port-au-Prince. It once was a coastal village but, like the lost city of Atlantis, the original Croix-des-Bouquets fell into the sea during one of the many earthquakes that have rocked Haiti since the dawn of time. The Port-au-Prince earthquake of June 3, 1770, was so strong that the tsunami waves it caused turned the earth along the coast into mud incapable of supporting buildings, and so the entire town slipped under the water. According to the history books, only three hundred people were killed by the tremor itself because a deep rumbling preceded it. They were warned that time. But in the fires and famine that followed, an estimated thirty thousand escaped slaves perished. What can I say? Mother Nature has never given Haiti a break.

My ancestors relocated Croix-des-Bouquets inland to the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac, a valley that extends all the way across the island, into the Dominican Republic. The soil there is naturally fertile and the valley is known for its agriculture. This changed the focus of the villagers from fishing to farming. Over the next two hundred years, the town evolved into two distinct halves: one was agricultural and the other industrial. They were divided by the center of town, literally and symbolically. In the middle was where all commerce was done, along a crowded section of road crammed with vendors selling their goods. The vendors built shacks there and later low buildings with storefronts.

Over time, the two sides of town also came to divide the “haves” from the “have-nots.” Those families who tended farms and passed them down through the generations were wealthy, because their land provided food to the rest of the country. Those who made clothes or other goods by hand weren’t as lucky. As the rest of the world industrialized and handmade items became outdated, those families fell further behind.

I was born on October 17, 1972. My family lived in the formerly industrial side of the village, in a place called La Serre, which by that time resembled the Juhu slums of Mumbai that were captured so well in the film Slumdog Millionaire. There was no infrastructure to speak of, so neighbors looked out for each other as best they could. We did not have electricity; we did not have centralized health care or local clinics of any kind. My mother will be the first to tell you that my birth was not an easy one.

I was not a small baby, so she was in pain. And I did not come quickly, so her pain was not brief. After hours of contractions, she was near delirious, but I would still not come because my large head (so I am told) had become stuck in her birth canal. The village midwife did what she could: she used forceps to grip the sides of my skull but she could still not guide me clear. It’s not like there were superprofessionals doing this stuff in Croix-des-Bouquets.

As the clock ticked and my mother continued to cry out in pain, the midwife lost her patience.

“Woman!” she yelled, right in my mother’s face. “Shut your tra

p now! Do not yell at me! I am not the one who got you pregnant!”

My father waited outside the hut, pacing and listening, unsure of what to do. Inactivity did not sit well with my father, because he was a man of action and a man of words, like his father before him. The two of them represent the pillars of my character. My grandfather had devoted himself to leading his village as their Vodou priest. My father chose to lead as well, devoting himself instead to Christianity, against his father’s wishes. In this moment of need, he turned to his faith.

As my mother continued to cry out helplessly, my father sat quietly and prayed until he found the answer. He entered the hut, put some water on the fire to boil, and sat down beside my mother. He opened his Bible to Psalm 23 and tore out the page. He cut the paper into small pieces, dropped them into the water, and stirred the concoction as the women stared in disbelief.

The midwife said what my mother could not. “Are you crazy? Why are you cutting your Bible?”

“Silence!” he shouted.

When the psalm had dissolved, he let the water cool.

Then he made my mother drink it.

“This will ease your pain,” he said.

Two hours later I was born. My father gave me the gift of words before I even left my mother’s womb.

PSALM 23

The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not be in want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures,

He leads me beside quiet waters.

He restores my soul.

He guides me in paths of righteousness

for His name’s sake.

Even though I walk

through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil,

for You are with me;

Your rod and Your staff,

they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me

in the presence of my enemies.

You anoint my head with oil;

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and love will follow me

all the days of my life,

and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

My parents named me Jeannel Wyclef Jean, a name that honors two rebel leaders in the history of man. The first is John Wycliffe, who was born in England in the 1320s and became a theologian, a preacher, and a religious reformer. Wycliffe and his followers were called the Lollards and they did not agree with the Roman Catholic Church’s idea of the role of the clergy. At the time, the Bible used by the Catholic Church was Latin, which allowed the church to control how its meaning was interpreted. The average churchgoer in England didn’t speak Latin, so they believed what they were told.

Wycliffe did not believe that a select group of men should be allowed to withhold the words of the Bible from their fellow men. He believed that they should be free to learn from the book directly. He believed, as I do, that all men must be their own teachers and be free to discover knowledge from the source because this is the only path to truth.

John Wycliffe has been referred to in religious history as the Morning Star of the Reformation. He was the earliest to question the rule of the clergy over the lives of man. He was ahead of his time: his writings planted the seeds of the Protestant Reformation that took hold in Western Europe two hundred years later. He was a man of both words and action, so in his fifty years on Earth, he put his beliefs into practice by initiating the first translation of the Bible into everyday English. In the scholarly Christian circles of his day, he argued that the scriptures be held in higher authority over both the papacy and the monks in man’s quest for God. Wycliffe began a translation of the Bible from the Vulgate, the fifth-century Latin version of the Bible used by the Catholic Church of the day. There is no way for historians to be certain, but they believe that John Wycliffe translated the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John himself and perhaps he completed the entire New Testament. His associates and his assistant, John Purvey, worked on translating the Old Testament and finished the resulting Wycliffe’s Bible in 1384.

His Bible, written in everyday English, had great influence due to the clarity, beauty, and strength of its language. Wycliffe taught that the privileged hierarchy of the clergy should be replaced with priests who chose a life of poverty, so his followers took no vows and received no consecration. They walked the countryside barefoot, in pairs, wearing long red robes and carrying staffs, preaching the sovereignty of God.

The other man I am named after is Toussaint L’Ouverture, a slave who became a general of the people and led Haiti to freedom from foreign rule in the late 1700s. He was freed by his French master and became a high-ranking officer in the Freemason organization in Saint-Dominigue, a French colony on the island of Hispaniola, would eventually become Haiti. L’Ouverture organized thousands of slaves in the area into a guerilla army that rebelled against the French colonial rulers. This was the first step toward the emancipation of the nation. It is fitting that the name Toussaint means “all souls opening.”

My father fused theology and leadership in my name, and it is no accident that he chose a rebel like Toussaint L’Ouverture to represent strength. My father was man of faith like his father, yet he chose to rebel against him. Where my grandfather found his path in life through Vodou, the native religion of the Haitian people, my father found his by embracing Christ—and defying his father’s beliefs. In that way, my father, Gesner Jean, was a typical teenager.

One day when he was eighteen, Gesner passed the Nazarene Church while he was walking through the streets of Port-au-Prince. According to him, he experienced a revelation. He saw the house of God with its doors opened before him and suddenly felt a light ignite inside him. Beyond the shadow of a doubt he understood what he must do with his life: he must become Protestant. He must “protest” Vodou and follow a path apart from his family’s beliefs.

Gesner walked into the church and joined their congregation that day. He could have done so and still practiced Vodou, because it isn’t uncommon for Haitians to do so. Some churches even integrate Vodou ritual into their Sunday services. But my father wanted no part of that; he wanted a clean break from tradition, so he renounced Vodou for life. There is one thing about my father that all who knew him will tell you: he always did what he vowed he would do. His father wasn’t happy to hear this news, but he took it respectfully. He told my father that he would always remain his son, though he saw their spiritual paths permanently diverging. There was definitely tension, because until his dying day, my father never spoke in depth of this decision. It was the moment that defined who he was, because he defied everything that his family had been up to that point. He told me about that time at a point in my life when he and I had our own problems. I was embarking on a path that was different from what he intended for me and we’d come to the crossroads where he, too, knew there was nothing he could do to change my mind. It is an interesting place for a father and a son because it’s a standoff. And because you’re of the same flesh, you know instinctually that your opponent is not going to give. And so you both walk away with respect and no harm done, because if you do anything else, it will be mutually assured destruction. So what I’m saying to you is that I believe that my grandfather respected my father’s decision, but he let it be known that he denounced it completely. Like father, like son: Gesner’s father was a spiritual leader, so in the end, he wanted that for his son, and he was willing to accept it, even if that meant that his son was going to become a leader in an institution that he rejected. And in a way, that is what passed between my father and me.

My father, Gesner Jean, was a born leader, just like his father. Even in his youth Gesner was the type of man who commanded the attention of his peers, so it didn’t take very long for him to become influential in the congregation of the church he’d just joined. He decided to become a licensed minister, because the Nazarene Church’s policy of shared power between the people and the clergy, and between the local churches and the greater denomination, echoed his

belief in equality and democracy. The church allows men and women to become ministers and their vow is to teach the word, to administer the holy sacraments, and to guide their community.

My father had been in the church for several years before I was born and had gotten far enough along in his education that he was granted a visa to visit a Nazarene Church in America to continue his studies. The church was founded in 1908, in Pilot Point, Texas, with Haiti accounting for the second-highest number of denominations in the world, after the United States. My father had other plans for that visa, though.

He planned to disappear.

After I was born, and my brother, Sam, two years later, my father’s main concern was finding us a better life, somewhere safer than Haiti. He did not see good times ahead after the election of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who came to power following his father, François’s, death in 1971. Nothing was going to change under the absolute power rule of the younger Duvalier. Speaking out against the government in any form was considered treason. Even a preacher could be arrested and executed without a word if one of his sermons was interpreted as being anti-Duvalier.

Gesner Jean did what he had to do: he deceived the church, he received his visa, and he went with his wife, Yolanda, to America, leaving their two kids, Sam and me, in Haiti. They settled as illegal immigrants among the Haitian community in the Marlboro Projects of Coney Island, Brooklyn, and once they settled, they had my brother Sedek. He had US citizenship by birth, and this in turn allowed my parents to become citizens through what has come to be called “maternity citizenship.” When illegal immigrants have a child in the United States, that child becomes what is called an “anchor baby,” which allows the parents to remain in the country and the entire family to apply for citizenship behind the infant’s legal right as a citizen. In 2008, by one estimate, there were something close to four hundred thousand anchor babies born in the States that year, all of whom allowed immigrant families a chance to bring other relatives into the country, leading to an unstable US population. It isn’t as easy as it used to be, but my parents did it, and once they got that foothold, they relocated my brother Sam and me, and then added to our family. My sister Melky came after Sedek and then, in their older days, my parents had my little baby sister, Rose.

Purpose

Purpose